Road to Prizren

for our last night in Belgrade, we decide to try the splavovi : the bars and nightclubs on boats on the banks of the Sava river. Sander, the dutch journalism student who’s staying at our youth hostel as well joins us. we warn him that so far, we haven’t been too lucky with the nightlife in Belgrade but he doesn’t really mind. it’s past 9 when we find ourselves waiting for a bus that will never come to bring us on the other side of the river. it takes us a long time and a lot of talks between us and with anyone willing to help us out before we finally find and climb down the stone stairs leading to the bank of the Sava. there, trying to avoid to walk on syringes and to disturb a few fishermen, we finally find the main alley leading to the splavovi and the said splavovi. naturally, they’re all closed.

starving and tired, we eventually walk back to the center. the first restaurant we aim for is closed and most other open places are only bars, we can already picture ourselves eating old cookies for dinner at our hostel. our last try before giving up leads our steps to Francuska and the metal gates of a tall and old building surrounded by a garden. a quick glance shows us that the terrace is closed but when we enter in the building, a waiter leads us in the underground restaurant. we’re almost alone in the big room, classy in a deliciously old-fashionned way. in our guide, we soon read that we’ve landed in the Klub Knjizevnika, one of the oldest restaurants in town, which used to welcome the intellectual, political and even dissident elite during Tito’s times. we might not have the faintest luck in finding good bars, but, counting the « ? »– the oldest tavern in town — and this one, we’re definitely spoiled with the restaurants and food here.

****

the incence scent strikes me, as we enter the dimly lit tiny chapel. standing in front of a turning book holder, a monk sings the orthodox ritual prayers in serbian. I’m hypnotized by the way the light right above him softens his face and for a while, I can only look as his lips moving and his fingers turning the pages. another monk approaches the light and turns the book holder, while the first one makes a sign to a monk I can’t see, probably to signify him when his turn will come. at last, I can detach my eyes from the book holder to look at the room, which is barely big enough for seven monks, let alone seven monks and five journalists. I’m not sure that it was a good idea to ask to come to their service, I feel like we’re a bunch of ruthless invaders violating their privacy, but finally, the soft orange light on the monks’ faces makes me partially change my mind, after all, our job is to invade privacies to tell our stories. I can only suppose that as long as we do it respectfully, I should be thankful for being there and sharing these precious moments. I don’t take any picture, but I fix the paintings everywhere on the walls, I fix the icons and candles, I fix the melodies and the words of their prayers and most of all, I fix the light on their faces.

****

« I hope we can be friends with France again… » the old teacher’s sparkling blue eyes are tinted with sadness and a bit of anger as he mutters one of the last sentence of our interview. here in gracanica, people remember that once, France and Serbia were close allies, friends even, and I feel as if their feeling of betrayal isn’t as much directed towards the EU as it is towards the french goverment. our diplomacy has been eager to recognize Kosovo’s independancy, despite the UN law and the Badinter commission and to understand better the serbian resent, Am?lie and I have to try to imagine a similar situation in France, which we can’t really, so we listen.

for some people we talked to in Belgrade, the serbs of Kosovo shouldn’t be stubborn and ought to leave this village deprived of water, electricity and future for the youth, but we realize that this isn’t even a question for the old teacher whose whole life has been and will be here. no matter what, it’s the place he can still call home. our view was slightly different in Belgrade, but here, it’s simply a matter of living in normal conditions, it’s a matter of not wanting to be slowly — or violently in a recent past — chased from home.

****

« we’ll be home soon », st?phane says with a smile, as he looks through the window. our bus is driving on the boulevard in front of the yellow train station, and yes, soon enough, it will stop at his terminus by the park. I smile back, we’re arriving in Belgrade but this time, we’re familiar with our surroundings and it really feels like coming home.

****

[dewplayer:http://uncover.free.fr/zix/blindwilliemctell.mp3]

Bob Dylan – Blind Willie McTell

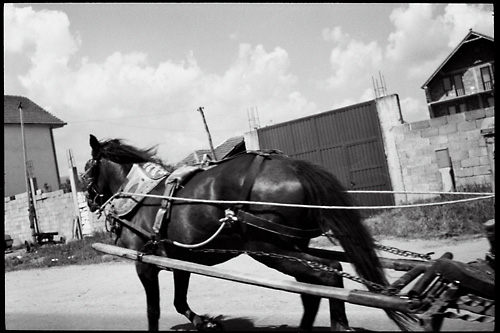

in every bus where I sit, I choose the window side and I watch every instant of life I can, every tree and every house, every person and every shop — I watch my own road movie going by. I want to fix it all, I want to show it all, I want to stop everywhere, in the serbian forests, along the mountain lakes near the border, in the fields and villages we cross. I can’t grasp it all, I can’t just stand anywhere and for a while, gaze around and feel the time flow away in an endless haemorrhage.

how many kilometers from Paris to Belgrade and back? how many hours from Belgrade to Pristina? how many buses have we climbed in?

and I had to come back somewhere, after more than eight hundred instants when I thought I could stop the time. I guess that this somewhere was home after all, yet, I don’t feel like here and now really is home. home has been nowhere and anywhere for a couple of weeks, and that’s precisely how I’ve loved it, how I’ve always longed it to be.

where do I want the next train to take me? how many kilometers from here to that place in me where I truly was?